In-class Example: The Pendulum#

In the last homework, you integrated a finite-amplitude pendulum and looked at the energy conservation properties. Now we’ll look at the FFT of the pendulum.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Here’s a simple class that creates a pendulum and can integrate it using fixed timesteps. It is important that our data be regularly spaced for the FFT.

class Pendulum:

""" a simple pendulum (w/o the small angle approximation).

Here, theta0 is in degrees"""

def __init__(self, theta0, g=9.81, L=9.81):

self.theta0 = np.radians(theta0)

self.g = g

self.L = L

self.t = None

self.theta = None

self.omega = None

def period(self):

""" return the period up to the theta**2 term """

return 2.0*np.pi*np.sqrt(self.L/self.g)*(1.0 + self.theta0**2/16.0)

def rhs(self, theta, omega):

""" equations of motion for a pendulum

dtheta/dt = omega

domega/dt = - (g/L) sin theta """

return np.array([omega, -(self.g/self.L)*np.sin(theta)])

def integrate(self, dt, tmax):

"""integrate the equations of motion using 4th-order

Runge-Kutta. Here, theta0 is the initial angle from vertical,

in radians.

Note: we use uniform steps here -- this is important to allow

for an FFT (which needs uniformly spaced samples).

"""

# initial conditions

t = 0.0

theta = self.theta0

omega = 0.0 # at the maximum angle, the angular velocity is 0

# store the history for plotting

t_s = [t]

theta_s = [theta]

omega_s = [omega]

while t < tmax:

# get the RHS at time-level n

thetadot1, omegadot1 = self.rhs(theta, omega)

thetadot2, omegadot2 = self.rhs(theta + 0.5*dt*thetadot1,

omega + 0.5*dt*omegadot1)

thetadot3, omegadot3 = self.rhs(theta + 0.5*dt*thetadot2,

omega + 0.5*dt*omegadot2)

thetadot4, omegadot4 = self.rhs(theta + dt*thetadot3,

omega + dt*omegadot3)

theta += (dt/6.0)*(thetadot1 + 2.0*thetadot2 +

2.0*thetadot3 + thetadot4)

omega += (dt/6.0)*(omegadot1 + 2.0*omegadot2 +

2.0*omegadot3 + omegadot4)

t += dt

# store

t_s.append(t)

theta_s.append(theta)

omega_s.append(omega)

self.t = np.asarray(t_s)

self.theta = np.asarray(theta_s)

self.omega = np.asarray(omega_s)

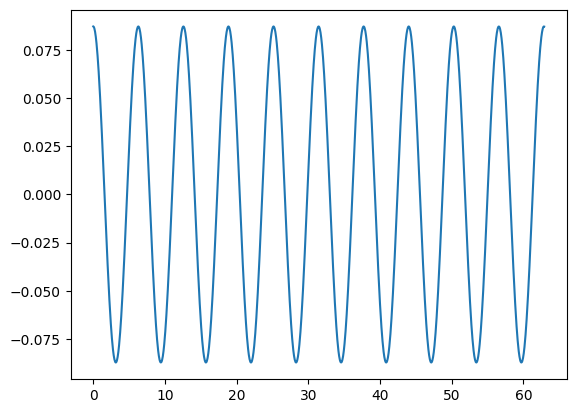

Let’s make a model. We’ll use the expansion of the period with \(\theta\) to estimate the period and try to integrate for an even number of periods.

p = Pendulum(5)

period = p.period()

tmax = 10 * period

p.integrate(0.05, tmax)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(p.t, p.theta)

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f2bf48cde90>]

Now let’s compute the FFT of this and see if we can identify the frequency. The frequency should be at

nu = 1.0 / p.period()

nu

np.float64(0.15907922699241395)

What happens to our FFT if we don’t integrate for exactly a multiple of the period? Then our time-series is not periodic. How does this manifest itself in the FFT?