Floating Point#

Storage overview#

We can think of a floating point number as having the form:

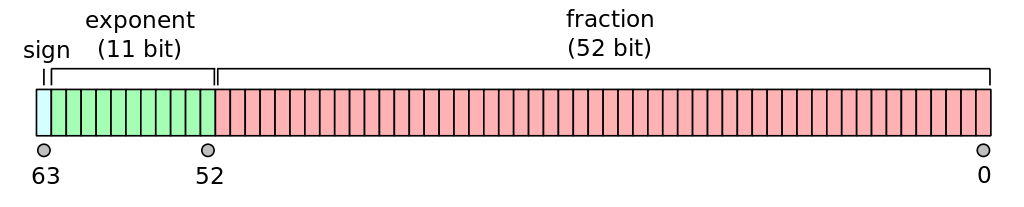

Most computers follow the IEEE 754 standard for floating point, and we commonly work with 32-bit and 64-bit floating point numbers (single and double precision). These bits are split between the significand and exponent as well as a single bit for the sign.

Here’s the breakdown for a double type:

Fig. 5 (source: wikipedia)#

Since the number is stored in binary, we can think about expanding a number in powers of 2:

In fact, 0.1 cannot be exactly represented in floating point:

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

int main() {

double a = 0.1;

std::cout << std::setprecision(19) << a << std::endl;

}

Note

Here we are using std::setprecision from the iomanip library to force the

output to have more decimal places.

Precision#

With 52 bits for the significand, the smallest number compared to 1 we can represent is

but the IEEE 754 format always expresses the significant such that the

first bit is 1 (by adjusting the exponent) and then doesn’t need

to store that 1, giving us an extra bit of precision, so the

machine epsilon is

We already saw how to access the limits of the data type via

std::numeric_limits. We call this number machine epsilon.

It is the smallest number that, when added to 1.0 gives a number

distinct from 1.0. We can use the == operator to check this.

#include <iostream>

#include <limits>

int main() {

double x{1.0};

double eps{1.11e-16};

// is x + eps the same as x?

bool test = x + eps == x;

std::cout << "x + eps == x: " << test << std::endl;

// the C++ standard library can also tell us epsilon

std::cout << "epsilon = " << std::numeric_limits<double>::epsilon() << std::endl;

}

Note that this is a relative error, so for a number like 1000 we could only add

1.1e-13 to it before it became indistinguishable from 1000.

Note that there are varying definitions of machine epsilon which differ by a factor of 2.

Range#

Now consider the exponent, we use 11 bits to store it in double precision. Two are reserved for special numbers, so out of the 2048 possible exponent values, one is 0, and 2 are reserved, leaving 2045 to split between positive and negative exponents. These are set as:

converting to base 10, this is

Testing for equality#

Because of roundoff error, we should never exactly compare two floating point numbers, but instead ask they they agree within some tolerance, e.g., test equality as:

For example:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

double h{0.1};

double sum{0.0};

// later well learn how to do a loop, but for now

// we'll explicitly add 10 h's

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

sum += h;

std::cout << "sum == 1: "

<< (sum == 1.0) << std::endl;

std::cout << "|sum - 1| < tol: "

<< (std::abs(sum - 1.0) < 1.e-10)

<< std::endl;

}